Ciągłe monitorowanie w SSc‑ILD

Wysoce zmienny przebieg śródmiąższowej choroby płuc związanej z twardziną układową (SSc-ILD) wymaga stałego, regularnego monitorowania w celu zapewnienia wczesnej interwencji zapobiegającej progresji choroby1–4

CZYNNIKI RYZYKA PROGRESJI W SSc‑ILD

| Płeć |

|

| Wiek |

|

| Czas trwania choroby |

|

| Rozległość choroby |

|

| Podtyp SSc |

|

| FVC | |

| DLCO |

|

| Parametry serologiczne: | |

| Zajęcie skóry |

|

| Objawy takie jak refluks/zaburzenia połykania |

|

Głównymi czynnikami ryzyka progresji ILD są: płeć męska, podtyp dcSSc, obecność przeciwciał przeciwko topoizomerazie I, wartość FVC <70% oraz rozległość włóknienia podczas oceny wyjściowej.19 W analizie bazy danych EUSTAR z 2020 roku FVC, obecność refluksu/zaburzeń połykania oraz mRSS podczas oceny wyjściowej były predyktorami istotnej progresji ILD w ciągu pierwszych 12±3 miesięcy.1

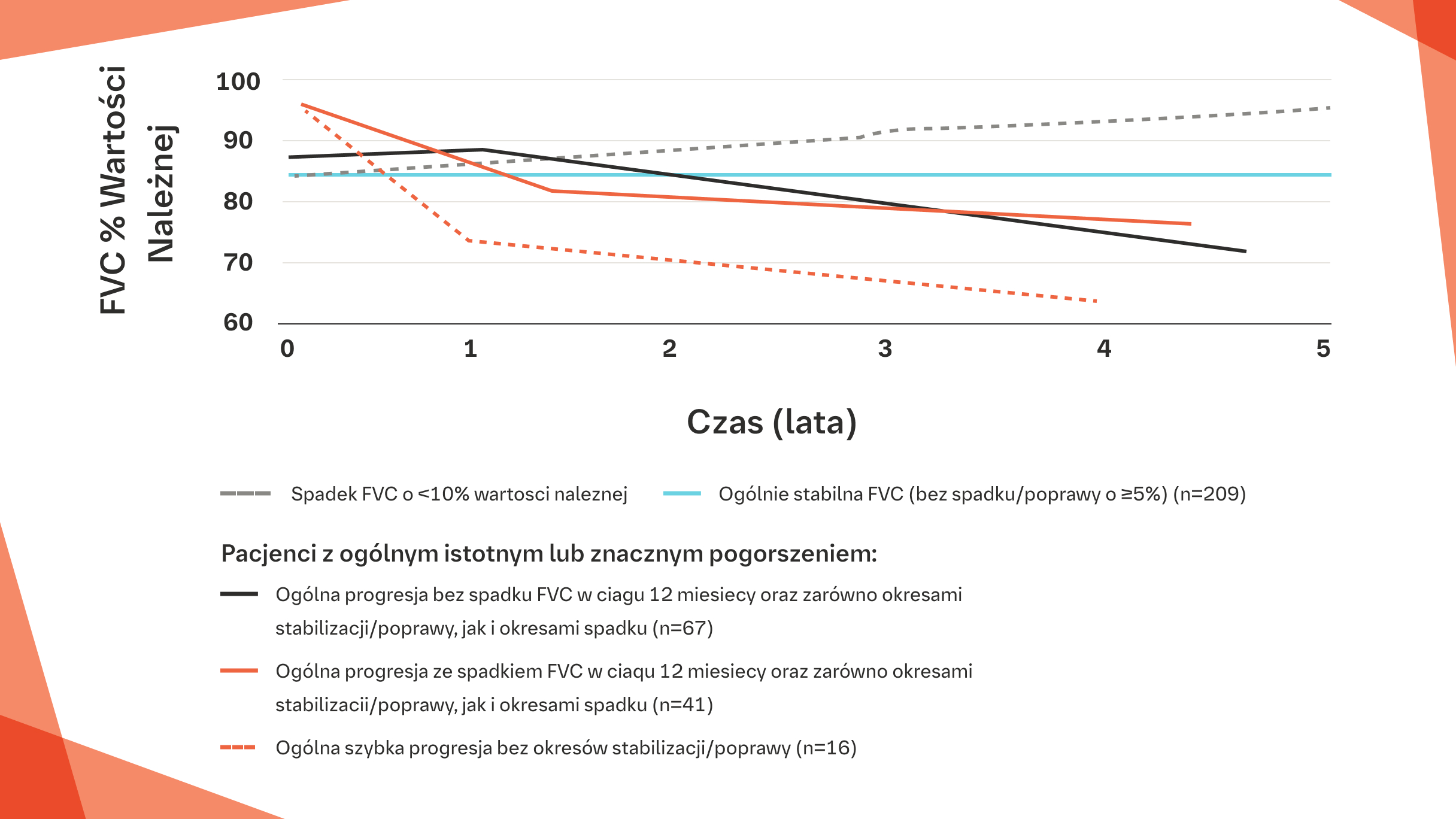

Zmienny przebieg choroby u pacjentów z SSc-ILD w bazie danych EUSTAR na podstawie skali zmian FVC (% wartości należnej) u poszczególnych pacjentów od oceny wyjściowej do końca 5-letniego okresu obserwacji.

Na podstawie: Hoffmann-Vold A-M, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020. Epub ahead of print dol: 10.1138/annrheumdis-2020-217455.

JAK MOŻNA PROWADZIĆ REGULARNE MONITOROWANIE ILD U PACJENTÓW Z SSc‑ILD?

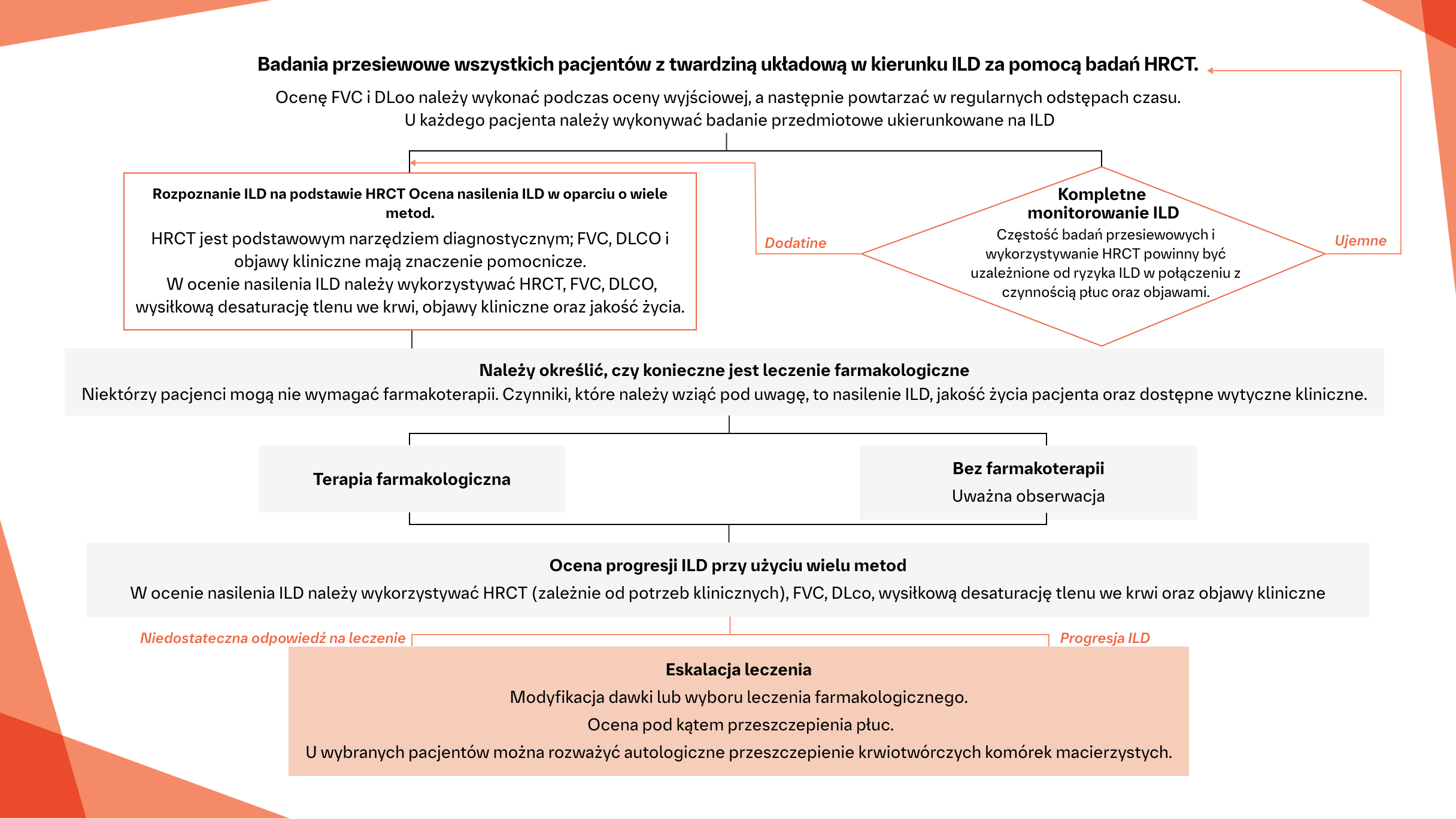

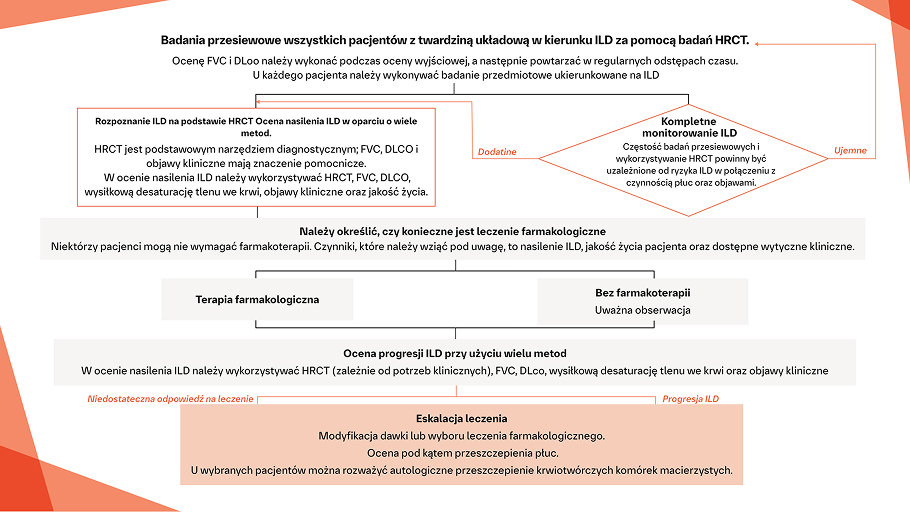

Algorytm monitorowania SSc‑ILD3

Algorytm ten zawiera krótkie podsumowanie konsensusu europejskiego opartego na dowodach, z uwzględnieniem uzupełniającego procesu Delphi, na podstawie opinii ekspertów z komitetu sterującego, w odniesieniu do identyfikacji i postępowania w SSc-ILD – do wykorzystania w praktyce klinicznej.

Na podstawie: Hoffmann-Vold AM, et al. Lancet Rheum. 2020;2:e71-e83.

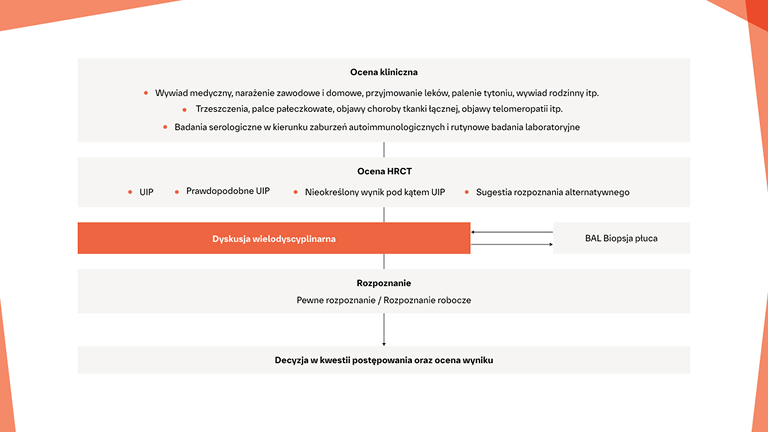

Jakie opcje postępowania należy rozważyć u pacjentów z SSc‑ILD?

Leczenie SSc‑ILD

Zapewnienie opieki paliatywnej/wspomagającej

Zespoły wielodyscyplinarne

Przypisy

-

CCL-18: ligand 18 chemokiny (motyw C-C); CRP: białko C-reaktywne; CTD-ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc związana z chorobą tkanki łącznej; dcSSc: rozlana skórna postać twardziny układowej; DLCO: pojemność dyfuzyjna płuc dla tlenku węgla; EUSTAR: Grupa Badawcza ds. Twardziny Europejskiej Ligi Przeciwreumatycznej; FVC: natężona pojemność życiowa; GER: refluks żołądkowo-przełykowy; HRCT: tomografia komputerowa wysokiej rozdzielczości; IL-6: interleukina-6; ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc; KL-6: Krebs von den Lungen-6; mRSS: zmodyfikowana skala oceny zmian skórnych wg Rodnana; PFT: badania czynnościowe płuc; scl-70: białko o masie 70 kDa związane z twardziną; SSc: twardzina układowa; SSc-ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc związana z twardziną układową.

-

Hoffmann-Vold AM, Allanore Y, Alves M, et al. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis- associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. Epub ahead of print: doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217455.

-

Hoffmann-Vold AM, Fretheim H, Halse AK, et al. Tracking impact of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis in a complete nationwide cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200;1258–1266.

-

Hoffmann-Vold AM, Maher TM, Philpot EE, et al. The identification and management of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: evidence-based European consensus statements. Lancet Rheum. 2020;2 e71–e83.

-

Distler O, Assassi S, Cottin V, et al. Predictors of progression in systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2020;55;1902026.

-

Winstone T, Assayag D, Wilcox P, et al. Predictors of mortality and progression in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. A systematic review. CHEST. 2014;146:422-436.

-

Cappelli S, Bellando Randone S, Camiciottoli G, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: where do we stand? Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:411–419.

-

Khanna D, Tseng C, Farmani N, et al. Clinical course of lung physiology in patients with scleroderma and interstitial lung disease: analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study Placebo Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3078–3085.

-

Asano Y, Jinnin M, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria, severity classification and guidelines of systemic sclerosis: Guideline of SSc. J Dermatol. 2018;45:633–691.

-

Moore OA, Goh N, Corte T, et al. Extent of disease on high-resolution computed tomography lung is a predictor of decline and mortality in systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology. 2013;52:155–160.

-

Nihtyanova SI, Schreiber BE, Ong VH, et al. Prediction of pulmonary complications and long–term survival in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66: 1625–1635.

-

Goh NS, Desai SR., Veeraraghavan S, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1248–1254.

-

Maher TM, Mayes MD, Kreuter M, et al. Effect of nintedanib on lung function in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: further analyses of the SENSCIS trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Nov 3. doi:10.1002/art.41576. Online ahead of print.

-

Volkmann, Elizabeth R, Tashkin DP, et al. Short-term progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis predicts long-term survival in two independent clinical trial cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019a;78:122–130.

-

Khanna D, Tashkin DP, Denton CP, et al. Etiology, risk factors, and biomarkers in systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:650–660.

-

Liu X, Mayes MD, Pedroza, C. et al. Does C-reactive protein predict the long-term progression of interstitial lung disease and survival in patients with early systemic sclerosis? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(8):1375–1380.

-

De Lauretis A, Sestini P, Pantelidis P, et al. Serum interleukin 6 is predictive of early functional decline and mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(4):435–446.

-

Volkmann, Elizabeth R, Tashkin DP, et al. Progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: the importance of pneumoproteins Krebs von den Lungen 6 and CCL18. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019b;71:2059–2067.

-

Wu W, Jordan S, Becker MO, et al. Prediction of progression of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: the SPAR model. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1326–1332.

-

Hoffmann-Vold A, Aaløkken TM, Lund MB, et al. Predictive Value of Serial High-Resolution Computed Tomography Analyses and Concurrent Lung Function Tests in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:2205–2212.

-

Guler, S.A., Winstone, T.A., Murphy, D., et al. Does systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease burn out? Specific phenotypes of disease progression. Annals ATS. 2018;15;1427–1433.

-

Chowaniec M, Skoczyńska M, Sokolik R, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: challenges in early diagnosis and management. Reumatologia. 2018;56:249–254.

-

Wells AU. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. La Presse Médicale. 2014;43:e329–e343.

-

Distler O, Volkmann ER, Hoffmann-Vold AM, et al. Current and future perspectives on management of systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:1009–1017.

-

Ryerson CJ, Cayou C, Topp F, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves long-term outcomes in interstitial lung disease: a prospective cohort study. Respir Med. 2014;108(1):203-210.

-

Kreuter M, Bendstrup E, Russell A, et al. Palliative care in interstitial lung disease: living well. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(12):968-980.

-

Maher TM, Wuyts W. Management of Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. Adv Ther. 2019;doi:10.1007/s12325-019-00992-9. [Epub ahead of print].

-

Sgalla G, Cerri S, Ferrari R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in patients with interstitial lung diseases: a pilot, single-centre observational study on safety and efficacy. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2015;2(1):e000065.

-

Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V. Spectrum of Fibrotic Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:958–968.

Materiały dla pacjentów po angielsku