Skutki CTD‑ILD

Śródmiąższowa choroba płuc (ILD) jest kluczowym czynnikiem powodującym wczesną śmiertelność w chorobach tkanki łącznej (CTD)1–6

WŁÓKNIEJĄCE CTD‑ILD CHARAKTERYZUJĄ SIĘ WŁÓKNIENIEM PŁUC, KTÓRE NIESIE ZE SOBĄ RYZYKO WCZESNEGO ZGONU1–5

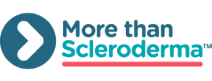

5‑letnie wskaźniki śmiertelności w CTD‑ILD7–13

Szacunkowe wskaźniki śmiertelności dla różnych CTD-ILD różnią się w poszczególnych badaniach. Przedstawione poniżej 5-letnie wskaźniki śmiertelności oparte są na szeregu różnych oszacowań pochodzących z różnych badań7–13

5-letnie wskaźniki śmiertelności stanowiące wartości środkowe z zakresów 5-letniej śmiertelności w CTD-ILD: 5-letnie wskaźniki śmiertelności RZS-ILD: 35%–39%;7,8 SSc-ILD: 10%–18%;9 ILD związana z pierwotnym zespołem Sjögrena:

5-letnie wskaźniki śmiertelności 12%–16%;10–12 PM/DM/CADM (zapalenie wielomięśniowe/zapalenie skórno-mięśniowe/klinicznie amiopatyczne zapalenie skórno-mięśniowe): 35%13

PAMIĘTAJ O CZYNNIKACH RYZYKA WCZESNEGO ZGONU, OCENIAJĄC SWOICH PACJENTÓW Z CTD-ILD

Czynniki ryzyka wczesnego zgonu w CTD-ILD | |

| HRCT | |

| Czynność płuc | |

| Zmienne demograficzne | |

Na obecne metody monitorowania czynności płuc w CTD-ILD miały wpływ badania IPF, w których spadek FVC i DLCO w seryjnych pomiarach był predyktorem wcześniejszego zgonu21

DLCO <40%, FVC <60% i restrykcyjny stosunek FEV1/FVC są predyktorami znacznego wzrostu śmiertelności w SSc21

ROZLEGŁOŚĆ ZMIAN TYPU „PLASTRA MIODU” W HRCT, A TAKŻE WARTOŚĆ DLCO, SĄ WYRAŹNIE ZWIĄZANE ZE ŚMIERTELNOŚCIĄ WE WŁÓKNIEJĄCYCH CTD‑ILD19,22

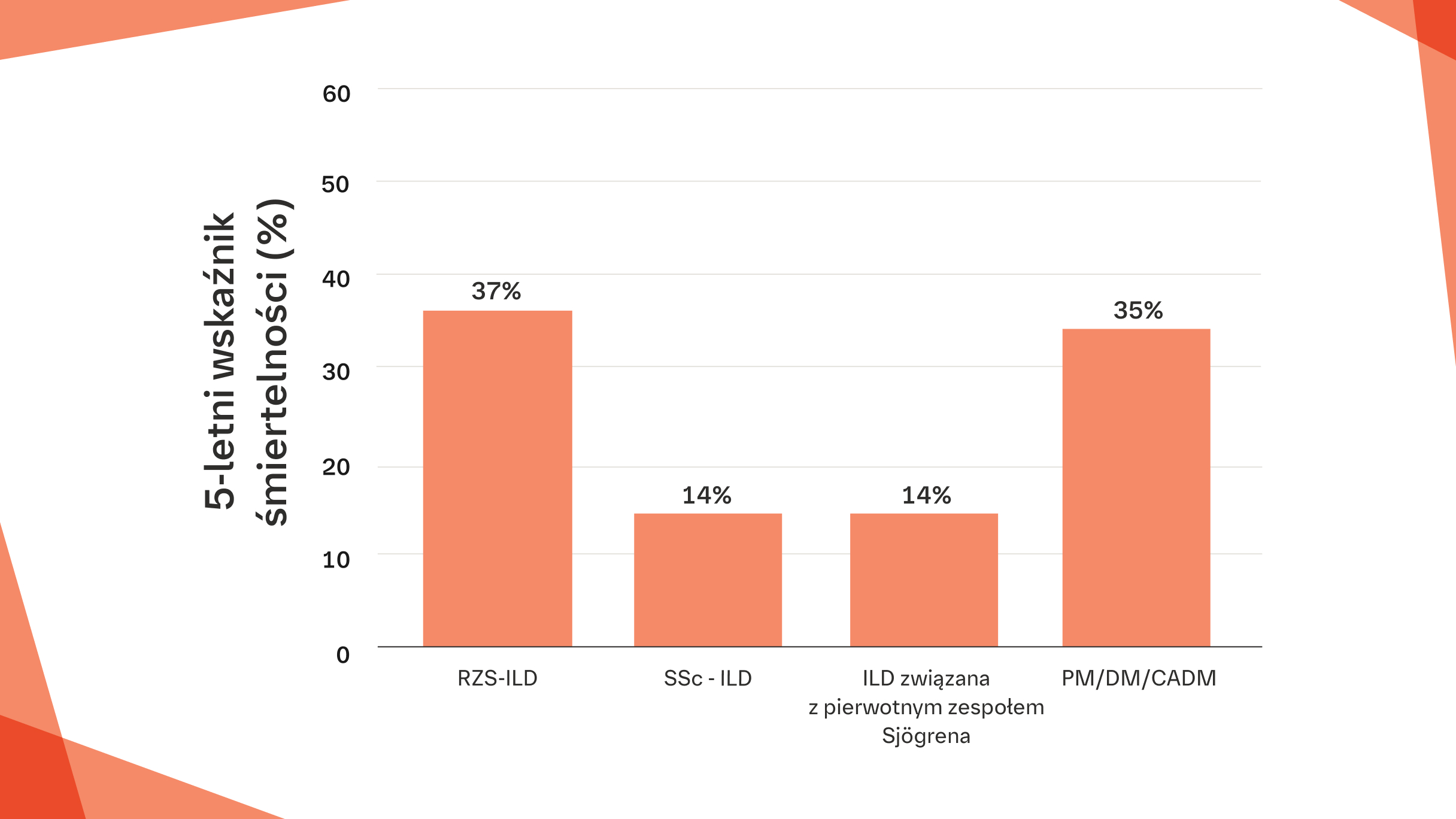

Obecność zmian typu „plastra miodu” w badaniu HRCT jest związana z większą długoterminową śmiertelnością wśród pacjentów z CTD-ILD w porównaniu z pacjentami bez zmian typu „plastra miodu” (p<0,001)20

Przeżycie 10-letnie u pacjentów z CTD-ILD ze zmianami typu „plastra miodu” lub bez takich zmian.

Na podstawie: Adegunso ye A. et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019:16:580-588.

Sprawdź, jak oceniać cechy radiologiczne CTD-ILD za pomocą badania HRCT

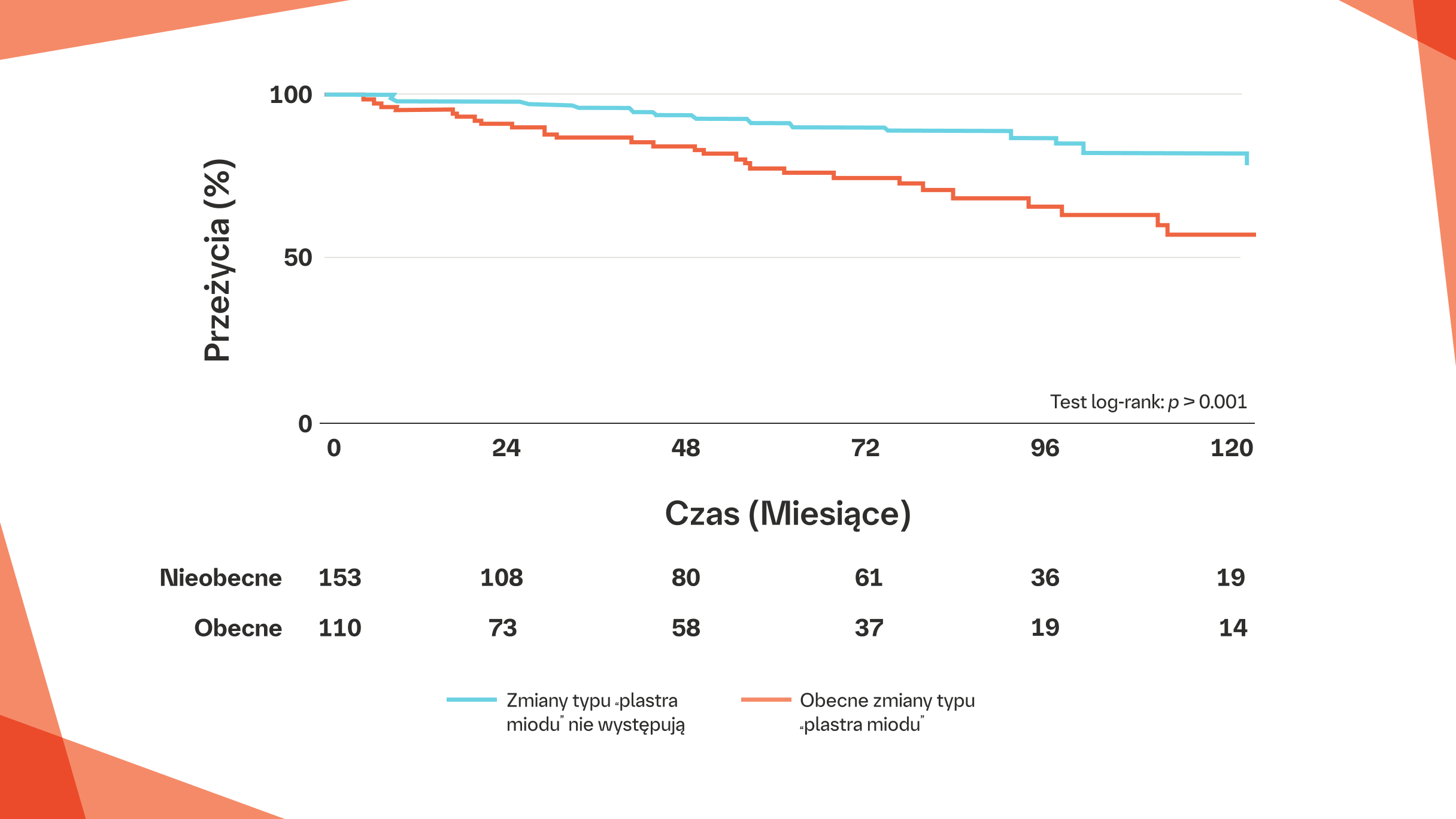

Niższa wyjściowa DLCO i zmniejszenie DLCO są związane ze zwiększoną śmiertelnością we włókniejącej CTD‑ILD18,19

CHOĆ NAGŁE ZAOSTRZENIE ILD WYSTĘPUJE RZADKO, JEST TO ŚMIERTELNE ZAGROŻENIE W PRZEBIEGU CTD‑ILD, KTÓRE MOŻE POJAWIĆ SIĘ W KAŻDEJ CHWILI23-27

Na podstawie danych dotyczących pacjentów z IPF można przyjąć, że nagłe zaostrzenie ILD jest najprawdopodobniej wywoływane przez ostre zdarzenie, takie jak zakażenie.28

Stwierdzono, że kaszel i duszność wiążą się z frustracją, wstydem, złością i izolacją wśród pacjentów, co prowadzi do rezygnowania z aktywności dających radość, takich jak spacer, taniec czy zabawa z dziećmi31

Kaszel związany z ILD negatywnie wpływa na funkcjonowanie fizyczne, udział w życiu społecznym, czynności życia codziennego i jakość snu31

Duszność ma negatywny wpływ na zdolność pacjentów do wykonywania codziennych czynności oraz na priorytety życiowe31

CTD-ILD wiąże się zarówno z krótkoterminową codzienną niepełnosprawnością, jak i z długoterminowymi trudnościami w planowaniu życia31

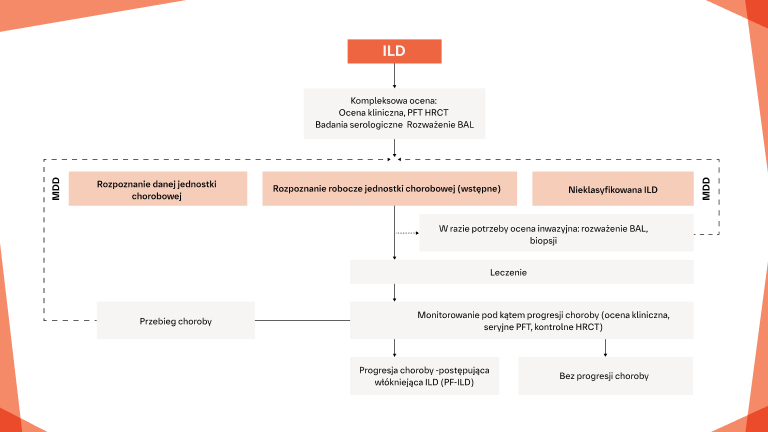

Jak zidentyfikować włókniejącą ILD możliwie jak najwcześniej u pacjentów z CTD?

Opisy przypadków CTD‑ILD

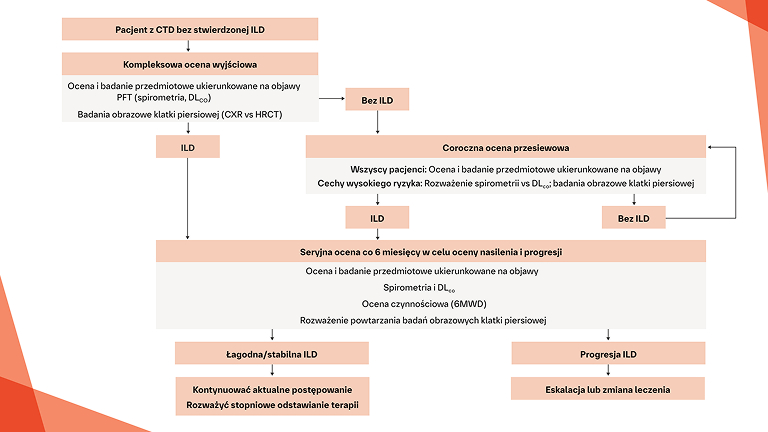

Wczesne i regularne monitorowanie pod kątem progresji ILD w CTD‑ILD

Postępowanie w postępującej włókniejącej CTD‑ILD

Przypisy

6MWD: dystans w 6-minutowym teście marszowym; CADM: klinicznie amiopatyczne zapalenie skórno-mięśniowe; CTD: choroba tkanki łącznej; CTD-ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc związana z chorobą tkanki łącznej; DLCO: pojemność dyfuzyjna płuc dla tlenku węgla; DM: zapalenie skórno-mięśniowe; FVC: natężona pojemność życiowa; HRCT: tomografia komputerowa wysokiej rozdzielczości; ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc; PM: zapalenie wielomięśniowe; RZS: reumatoidalne zapalenie stawów; RZS-ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc związana z reumatoidalnym zapaleniem stawów; SSc: twardzina układowa; SSc-ILD: śródmiąższowa choroba płuc związana z twardziną układową

-

Fischer A and Distler J. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease associated with systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(10):2673–2681.

-

Mathai SC and Danoff SK. Management of interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease. BMJ. 2016;352:h6819.

-

Wallace B, Vummidi D, Khanna D. Management of connective tissue diseases associated interstitial lung disease: a review of the published literature. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28(3):236–245.

-

Spagnolo P, Cordier JF, Cottin V. Connective tissue diseases, multimorbidity and the ageing lung. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1535–1558.

-

Vacchi C, Sebastiani M, Cassone G, et al. Therapeutic options for the treatment of interstitial lung disease related to connective tissue diseases. A narrative review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):407. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020407.

-

Maher TM, Wuyts W. Management of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Adv Ther. 2019;36(7):1518–1531.

-

Hyldgaard C, Hilberg O, Pedersen AB, et al. A population-based cohort study of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: comorbidity and mortality. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1700–1706.

-

Raimundo K, Solomon JJ, Olson AL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis – interstitial lung disease in the United States: prevalence, incidence, and healthcare costs and mortality. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(4):360–369.

-

Bouros D, Wells AU, Nicholson AG, et al. Histopathologic Subsets of Fibrosing Alveolitis in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis and Their Relationship to Outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1581–1586.

-

Palm Ø, Garen T, Enger TV, et al. Clinical pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, quality of life and mortality—a retrospective study based on registry data. Rheumatology. 2013;52:173-179.

-

Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary Manifestations of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:632–638.

-

Enomoto Y, Takemura T, Hagiwara E, et al. Prognostic Factors in Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Retrospective Analysis of 33 Pathologically–Proven Cases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73774.

-

Ji S-Y, Zeng F-Q, Guo Q, et al. Predictive factors and unfavourable prognostic factors of interstitial lung disease in patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis: a retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(5):517–522.

-

Tyndall AJ, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1809-1815. doi:10.1136/ ard.2009.114264.

-

Cassone G, Manfredi A, Vacchi C, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: lights and shadows. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):1082.

-

Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis–Interstitial Lung Disease–associated Mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:372–378.

-

Yazisiz V, Göçer M, Erbasan F, et al. Survival analysis of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome in Turkey: a tertiary hospital-based study. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(1):233–241.

-

Chan C, Ryerson CJ, Dunne JV, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of progression and mortality in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):192. doi: 10.1186/ s12890-019-0943-2.

-

Walsh SLF, Sverzellati N, Devaraj A, et al. Connective tissue disease related fibrotic lung disease: high resolution computed tomographic and pulmonary function indices as prognostic determinants. Thorax. 2014;69(3):216–222.

-

Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, et al. Computed Tomography Honeycombing Identifies a Progressive Fibrotic Phenotype with Increased Mortality across Diverse Interstitial Lung Diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:580–588.

-

Paschalaki KE, Jacob J, Wells AU, et al. Monitoring of Lung Involvement in Rheumatologic Disease. Respiration. 2016;91:89–98.

-

Geerts S, Wuyts W, de Langhe E, et al. Connective tissue disease associated interstitial pneumonia: a challenge for both rheumatologists and pulmonologists. Sarcoidosis Vasc Dif. 2017;34:326–335.

-

Kolb M, Bondue B, Pesci A, et al. Acute exacerbations of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(150):pii:180071.

-

Song JW, Hong S-B, Lim C-M, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(2):356–363.

-

Song JW, Lee H, Lee C, et al. Clinical Course and outcome of rheumatoid arthritis-related usual interstitial pneumonia. Sarcoidosis Vasc Dif. 2013;30:103–112.

-

Tomiyama F, Watanabe R, Ishii T, et al. High Prevalence of Acute Exacerbation of Interstitial Lung Disease in Japanese Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;239, 297–305.

-

Okamoto M, Fujimoto K, Sadohara J, et al. A retrospective cohort study of outcome in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Respiratory Investigation. 2016;54, 445–453.

-

Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis – An International Working Group Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:265–275.

-

Suda T, Kaida Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia associated with collagen vascular diseases. Resp Med. 2009;103:846–853.

-

Cao M, Sheng J, Qiu X, et al. Acute exacerbations of fibrosing interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue diseases: a population-based study. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:215.

-

Mittoo S, Frankel S, LeSage D, et al. Patient perspectives in OMERACT provide an anchor for future metric development and improved approaches to healthcare delivery in connective tissue disease related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD). Curr Respir Med Rev. 2015;11:175–183.

-

Saketkoo LA, MMittoo S, Huscher D, et al. Connective tissue disease related interstitial lung diseases and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: provisional core sets of domains and instruments for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 2014;69(5):428–436.

-

Saketkoo LA, Scholand MB, Lammi MR, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis–related interstitial lung disease for clinical practice and clinical trials. Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2020;5(2 Suppl):48–60.

-

Morisset J, Dubé B, Garvey C, et al. The Unmet Educational Needs of Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease: Setting the Stage for Tailored Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1026–1033.

-

Swigris JJ, Brown KK, Abdulqawi R, et al. Patients’ perceptions and patient-reported outcomes in progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(150):180075. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0075-2018.

-

Chowaniec M, Skoczyńska M, Sokolik R, Wiland P. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: challenges in early diagnosis and management. Reumatologia. 2018;56(4):249–254.

-

Cottin V, Brown KK. Interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc–ILD). Respir Res. 2019a;20(1):13.

-

Wells AU, Denton CP. Interstitial lung disease in connective tissue disease— mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:728–739.

Materiały dla pacjentów po angielsku